Chinese historical relics have never been silent specimens in museums. On the contrary, they constitute open texts spanning five thousand years, continuously releasing interpretive tension in contemporary life. As of July 2024, with the inclusion of the “Beijing Central Axis” in the list, the total number of World Heritage sites owned by China has reached 57 (UNESCO World Heritage Centre, 2024). This means that when you plan your next cultural trip, facing the scattered historical relics on this land is facing a general history of civilization written in bricks, stones, civil engineering, and mountains. The key is how to penetrate the surface of internet celebrities checking in and truly enter the historical context of these relics.

Palaces and Tombs of Chinese Historical Relics: Spatial Encoding of Power

The palace architecture is based on the Forbidden City in Beijing. The spatial order composed of over 9000 houses is essentially a materialized expression of Confucian ritual system. The evaluation of the World Heritage Committee: “The Forbidden City, as the highest imperial palace for five centuries, is an invaluable witness to the Chinese civilization of the Ming and Qing dynasties” (UNESCO World Heritage Centre, 2024). The key is that these buildings do not exist in isolation. Their creative logic permeates every dimension of pilgrimage, sacrifice, and daily life.

The burial system constitutes another important dimension. The military array layout of the Mausoleum of Qin Shi Huang and Terracotta Warriors shows the permanent structure of the imperial military organization. The Feng Shui site selection of the Ming Thirteen Tombs reflects the precise calculation of the concept of “unity of heaven and man” in the funeral field. These relics together form a complete network of meaning from birth to death. In other words, strolling among these historical relics, you are reading the political grammar of ancient China.

Grottoes and Temples of Chinese Historical Relics: The Accumulation of Beliefs

The Mogao Grottoes of Dunhuang in the arid area of northwest China have preserved murals and sculptures spanning over a thousand years. The current protection has entered the stage of ‘living heritage’. The combination of some movies and cave scenes in the digital display center solves the contradiction between “protection” and “interpretation”. The key is that this technological intervention delays physical decay and expands cognitive dimensions.

The Yungang Grottoes represent the pinnacle of Buddhist art in the 5th century. The sequence of statues in Longmen Grottoes reflects the style evolution from Northern Wei to Tang Dynasty. Dazu Rock Carvings is famous for its “secularization”, which integrates folk life scenes into religious narrative. These Chinese historical relics demonstrate how faith obtains eternal forms in rocks.

City Walls and Settlements: The Defense Wisdom of Rural Areas

Pingyao Ancient City preserves the urban layout of the Han ethnic group since the 14th century. The grandeur of its financial district buildings bears witness to the prosperity of China’s banking center in the 19th century. The Old Town of Lijiang is famous for its unique form of “no city wall” and its integration with Naxi culture.

The Earthen Building in Fujian Province and Kaiping Diaolou represent outstanding examples of folk wisdom. The World Heritage Committee pointed out that earthen buildings “embody a specific type of public life and defense organization” (UNESCO, 2008). These buildings perfectly combine residential functions with defense needs. What I mean is that these relics are not just tourist background boards, they still carry real local life to this day.

Gardens and Landscape of Chinese Historical Relics: The Poetic Dwelling of Literati

The Classical Gardens of Suzhou in Jiangsu Province have realized the ideal of “rebuilding the universe within a short distance”. The World Heritage Committee evaluates that “these gardens reflect the profound artistic conception of Chinese culture that takes inspiration from nature and transcends it” (UNESCO World Heritage Centre, 2024). The West Lake in Hangzhou, as a cultural landscape heritage, has influenced the aesthetics of East Asian gardens for hundreds of years with its “three sides of cloud mountains and one side of the city” pattern.

As a dual heritage of culture and nature, Mount Taishan has been the object of emperors’ chanting and literati’s chanting since ancient times. Mount Huangshan has become the spiritual source of landscape painting with its strange pines and rocks. These geographical spaces are not only natural landscapes, but also projection fields of cultural emotions.

Heritage: A Civilization Corridor Across Regions

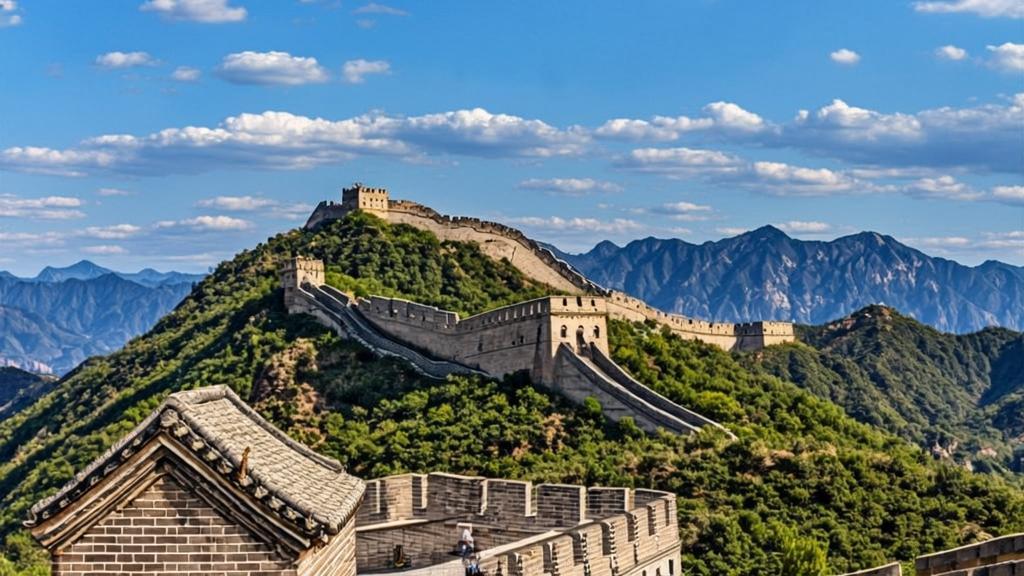

The Great Wall is not simply a military barrier. The discovery of Sogdian tombs and multilingual inscriptions along its route proves that this giant architectural belt is a corridor for cross-cultural trade. The Grand Canal is 2700 kilometers long. As the longest artificial waterway in the world, it undertook the important function of national grain transportation in the Ming and Qing dynasties (National Cultural Heritage Administration, 2014).

The Silk Road: The Road Network of Chang’an Tianshan Corridor spans 5000 kilometers, connecting ancient civilizations in the Central Plains and Central Asia. The geographical span of these linear Chinese historical relics forces travelers to adjust their observation scales. You need to understand the multiple facets of civilization between the Gobi Desert in the Hexi Corridor and the misty rain of the Jiangnan water network.

Methodology of Seeking: Beyond Catching Gaze

For true cultural travelers, visiting these relics requires a specific cognitive framework. Firstly, time selection is crucial. In winter, there are few tourists visiting the Great Wall, and the visual purity after snow is closer to the historical original. The park in the early morning often features local residents’ morning exercise activities, forming a unique “time stamp” with ancient buildings.

Secondly, literature preparation is indispensable. When you visit the Foguang Temple on Mount Wutai with architectural history materials, the details of those Tang Dynasty wooden structures will change from components to interpretable codes. Finally, it is recommended to establish a comparative perspective. After seeing the relics of different civilizations, you may be able to more keenly capture the unique spatial logic of these relics.

In short, the value of Chinese historical relics lies not only in their age, but also in their continuous participation in the construction of contemporary Chinese meaning. From the oracle bones of the Yin ruins to the newly listed central axis of Beijing, these remains are still in the process of being rediscovered.

References

UNESCO World Heritage Centre. (2024). – World Heritage List – China https://whc.unesco.org/en/list.

UNESCO. (2008). ‘Fujian Tulou‘ https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1113.

National Cultural Heritage Administration (2014). ‘Measures for the Protection and Management of the Grand Canal Heritage’, http://www.ncha.gov.cn.